Follow Randy Dadez and his family as they rebuild their lives. Read more stories in this series here.

On a Sunday morning seven weeks after the Lahaina fire, Randy Dadez sits on the couch in his FEMA-funded room at a Fairmont hotel in Wailea, a resort area about 45 minutes south of Lahaina, scrolling social media.

He is wearing his favorite Harley Quinn T-shirt, one of his only clothing items that survived the fire. At his feet are boxes of donated dinner sausages that the family has no way of cooking in a hotel room without any kitchen appliances.

“Three grand?” he exclaims, reading aloud from a Facebook advertisement for a one-bedroom apartment rental. “Are you kidding?”

The Dadezes had lived in a neighborhood where landlords charged rents that resort shuttle drivers, like Randy, and spa receptionists like his wife, Marilou, could afford. They paid $2,400 a month, including utilities, for a beige, two-bedroom ohana unit on Kaniau Road.

But rents like that don’t seem to exist anymore.

“Oh, how’s this!” Randy calls out. Another social media post has caught his eye, this one about a donations giveaway at a Lahaina beach park.

“Look how nice, the stuff that they’re giving out,” he says to his wife. “See? Shoes, boogie board, fishing poles. Look! Brand new bikes.”

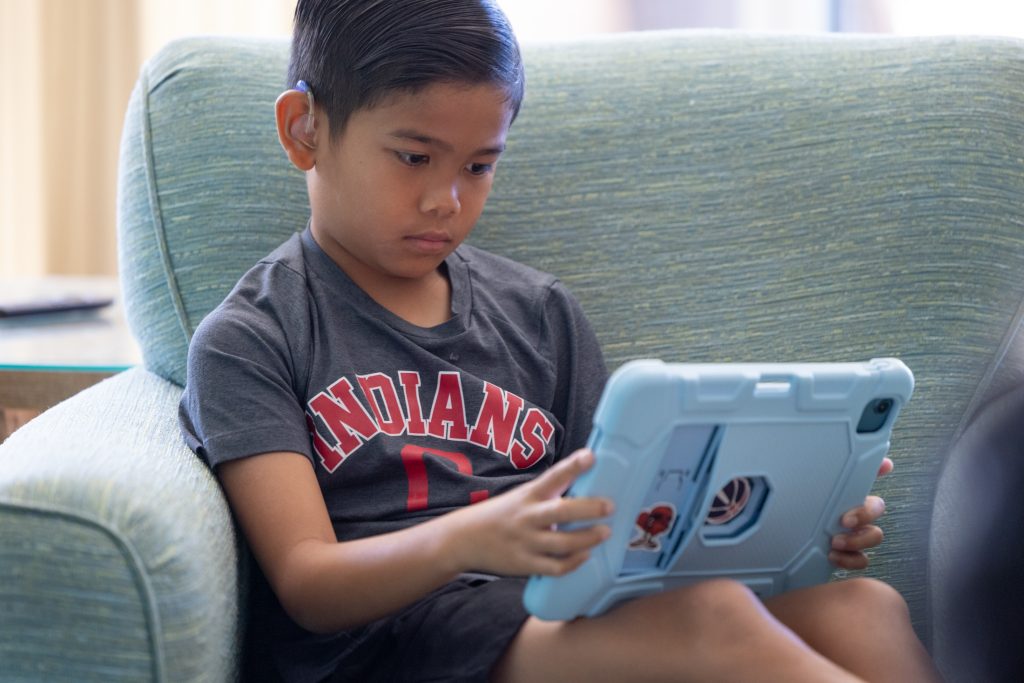

The couple’s 9-year-old son Kobe, who has been absorbed by a game on his iPad, jerks his head up.

“I want a fishing pole!” Kobe begs. “Dad, can we go there?”

Randy checks the time on his phone.

“Oh, man,” he says. “It started already. There’s so many people over there, it’s gone already. By the time we get there it will all be gone.”

Rebuild For The Next Generation

Randy Dadez had been saving up to rebuild the 1938 plantation house he grew up in on Hoapili Street when the Aug. 8 wildfire burned it down, too.

Four generations of Dadezes had lived under its corrugated metal roof, starting with his great-grandfather, who immigrated to Lahaina from the Philippines with his pregnant wife in 1924 to work in the town鈥檚 sugar fields.聽Randy’s father, an Air Force veteran and former martial arts fighter, lived in the house most recently, while Randy and his family rented a place a few streets away, in Lahaina鈥檚 Wahikuli subdivision.

Shaded by an old mango tree, the 85-year-old house — the nucleus of the extended Dadez family — stood two blocks from Lahaina鈥檚 famous Front Street. The backyard had a chicken coop and a garden of vegetables essential to Filipino cooking.

The house was uninsured when it went up in flames. Although the sliver of land it occupied had been valued at more than half-a-million dollars, the house itself was worth only $56,000, according to county property records.

It had been Randy’s dream to one day knock it down and build something new as an anchor of permanence and stability for his four kids, ranging from nine to 21 years old, who faced an uncertain future in Maui鈥檚 brutal housing market. In his vision, he and his wife Marilou, as well as his parents, would live there, too.

Suddenly, that vision has become urgent.

But reconstruction is now marred by the intricacies of a federally funded disaster cleanup. Local authorities have advised patience, predicting that it could be two years or more before property owners can begin to rebuild their homes in Lahaina.

‘People Are Dying In There’

Randy Dadez had been at work as a shuttle driver at a resort north of Lahaina on the evening of Aug. 8 when the fire started raging around the family’s rental house. His wife and kids were at home sound asleep. The heat from the flames woke them up and sent them into a frenzied rush to safety. Marilou does not drive, so it was up to her eldest daughter Rianna to drive the family out of the apocalyptic scene.

As his family escaped, Randy tried to get home. But there was a road block. A police officer wouldn鈥檛 let him enter his neighborhood.

鈥淚 can鈥檛 let you in because people are dying in there,鈥� Randy said the officer told him.

So he pulled a U-turn.聽He was on Honoapiilani Highway heading north when he recognized the license plate on the 2001 Honda Accord on the road ahead of him with his family inside.

The Dadezes spent the night sleeping in their cars in a parking lot at Kapalua Resort, where Randy drives tourists between their hotels and nearby attractions.

The next day the family drove south to Kahului, where they were taken in by members of the Seventh Day Adventist church. The Dadezes were shocked to find that it simply didn’t matter that in Lahaina they were Catholics or that they hadn’t attended a church service of any affiliation in many years. The congregation treated them as one of their own.

When the Dadezes arrived, a volunteer handed Marilou $800 in cash. The volunteer then showed her to a preschool classroom, where there were air mattresses, fresh pillows and sheets and new clothes and underwear for her and her family.

Marilou cried. Randy decided on the spot that he would start going to church again. The family lived in the church for two weeks.

鈥淚 want to say I owe them a lot, which I do,鈥� Randy says. 鈥淏ut then, you know, what I learned from them is it’s God that led me there to that church. It鈥檚 God that helped us. And I really thought about it. Well, whatever it is, whoever it is, it helped a lot, you know?鈥�

After the Dadezes moved out of the church and into a hotel room paid for by FEMA, they returned to the church every Saturday to attend the Sabbath day worship.

Going Back Home Brings Trauma And Closure

Three days after the fire, the family drove back to Lahaina to see what remained of their home.

Authorities posted at the neighborhood’s entry point let them in to scour the ruins of their rental property for photo albums, jewelry and their pet fish Bubbles.

But there was nothing to recover. Only ash and twisted metal.

鈥淚 wish I didn鈥檛 see it because it hurts,鈥� Marilou Dadez says.

But for Randy Dadez, seeing the wreckage helped him make sense of it all.

鈥淵ou ever heard of this thing called ghost feeling?鈥� Randy says. 鈥淲hen you lose a finger or your hand, it feels like it鈥檚 still there. That鈥檚 what it felt like. Until we could go back and see for ourselves, it felt like the house was going to be there. We had to see it ourselves for the reality to kick in.鈥�

While viewing the wreckage of their home provided the family some closure, Marilou says it probably also compounded her children鈥檚 trauma.

When school started in October, Kobe, the 9-year-old, burst into a fit of anxiety in front of his classmates, calling out for mom and dad. Their 12-year-old daughter Samara skipped lunch and hid in the bathroom during her first week of classes.

‘Nothing To Cry About’

In nearly 12 weeks of searching for a place to live, the family has come up with nothing. Nothing suitable for seven people (the family, plus the eldest daughter’s live-in boyfriend). Nothing they can afford.

With most of Lahaina鈥檚 13,000 residents displaced, prices are being driven up beyond the Dadezes’ means by twin pressures of swollen competition and a longstanding affordable housing shortage.

Above all, the family wants to stay together as they recover. But as time drones on, they’re finding it increasingly difficult to try to resume some version of normalcy while living in a hotel.

Marilou yearns to cook pork adobo and other Filipino meals for her family. But she doesn’t have access to a kitchen. And countertop appliances like rice cookers and hot plates are forbidden in the hotels.

Then there鈥檚 the looming stress of never knowing when they鈥檒l get a phone call saying they have 48 hours to move to another resort.聽In more than two months the family has moved three times, from the church to the Wailea resort and in late September to a Hyatt hotel in Lahaina.

Adding to the pressure are the financial losses from Randy being temporarily out of work while visitors stayed away from West Maui until a tourism reopening plan kicked in last month.

Marilou’s migraine headaches have grown more intense and more frequent, making it unlikely that she could soon return to her part-time job as a hotel spa receptionist. She describes the pain in her head as daily and disabling. And she wonders if the stress of an uncertain future could be to blame for her worsening symptoms.

Randy says he has cried just once in the aftermath of the disaster.

鈥淵ou ever heard of Mount Pinatubo?鈥� he says, referring to the volcano in the Philippines, where he was born on a U.S. Air Force base. 鈥淲hen that erupted, my cousins, my family over there, they were living in pig pens. The government gave them 鈥� one time 鈥� one bag of rice, a sardine can and water. That was it. That was the only help you got. So I have nothing to cry about.鈥�

Civil Beat鈥檚 coverage of Maui County is supported in part by grants from the Nuestro Futuro Foundation.