This Study Offers A New Way Forward In The Debate Over Feral Cats

To protect wildlife from free-roaming cats, a zone defense may be more effective than trying to get every feline off the street.

Should domestic cats be allowed to roam freely outdoors? It’s a contentious issue. Those who say yes assert that they’reĚýĚýand theĚý. Critics respond that free-roaming catsĚýĚýthat theyĚý.

´ˇ˛őĚýĚýĚýfamiliar with these clashing viewpoints, we wondered whether there was room for a more nuanced strategy than the typical yes/no standoff. In aĚý, we used camera traps at hundreds of sites across Washington, D.C., to analyze the predatory behavior of urban free-roaming cats. The cameras recorded all cats that passed them, so our study did not distinguish between feral cats and pet cats roaming outdoors.

Our data showed that the cats were unlikely to prey on native wildlife, such as songbirds or small mammals, when they were farther than roughly 1,500 feet from a forested area, such as a park or wooded backyard. We also found that when cats were approximately 800 feet or farther from forest edges, they were more likely to prey on rats than on native wildlife.

Since the average urban domestic cat ranges over a small area –Ěý, or Ěý– the difference between a diet that consists exclusively of native species and one without any native prey can be experienced within a single cat’s range. Our findings suggest that focusing efforts on managing cat populations near forested areas may be a more effective conservation strategy than attempting to manage an entire city’s outdoor cat population.

Cats On The Loose

Free-roaming cats are a common sight in Washington, D.C., which has . Like many cities, Washington has had its share ofĚý.

Professionals on either side of the free-roaming cat debate largely agree that cats are safest when kept indoors. An outdoor cat’s lifespan generally , compared with 10 to 15 years for an indoor cat. Free-roaming cats face numerous threats, including vehicle collisions and contact with rat poison. Acknowledging these risks, most animal welfare organizations encourageĚý.

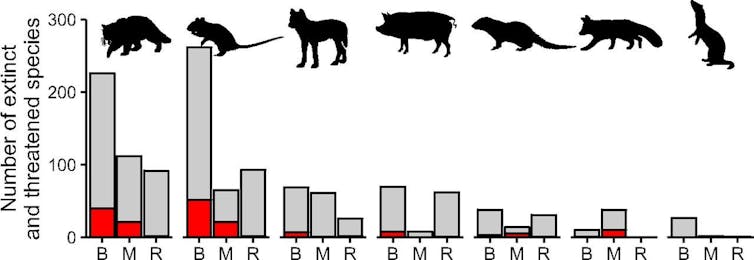

Similarly, there is little disagreement that cats hunt; for centuries humans have used them for rodent control. But invasive rats, which are often the target of modern rodent control,ĚýĚýto be easy prey for cats. In response, cats also pursue smaller species that are easier to catch. Studies have linked cats toĚýĚýand estimated that catsĚýĚýannually in the U.S. alone.

Disagreements arise around handling cats that already live outside. Population management programs often utilize trap-neuter-return, or TNR – a process in which cats are trapped, spayed or neutered and re-released where they were caught.

In theory, TNR limits population growth by reducing the number of kittens that will be born. In reality it is rarely effective, sinceĚýĚýto reduce the population, which is often not feasible. Regardless, reproduction itself is not what most worries conservation biologists.

Feline Invaders

Today the Earth is losing wild species at such a rate that many scientists believe it is experiencing itsĚý. In this context, free-roaming cats’ effects on wildlife are a serious concern. Cats have an instinctual drive to hunt, even if they are fed by humans. Many wildlife populations areĚýĚýin a rapidly changing world. Falling prey to a non-native species doesn’t help.

CatsĚýĚýbut will pounce on the easiest available prey. This generalist predatory behavior contributes to their reputation asĚý. In our view, however, it could also be a key to limiting their ecological impact.

Managing Cats Based On Their Behavior

Since cats are generalist predators, their wild-caught diet tends to reflect the local species that are available. In areas with more birds than mammals,Ěý, birds are cats’ primary prey. Similarly, cat diets in the most developed portions of cities likely reflect the most available prey species – rats.

While cats top the list of harmful invasive species,Ěý. In cities, rats spread disease, contaminate food andĚý. There aren’t many downsides to free-roaming cats preying on rats.

City centers haveĚý, which can live anywhere, including parks, subways, sewers and buildings. But native animals tend to stay in or nearĚý, like parks and forested neighborhoods. When cats hunt in these same spaces, they are a threat to native wildlife. But if cats don’t share these spaces with native species, the risk declines dramatically.

Conservation funding is limited, so it’s critical to choose effective strategies. The traditional approach to cat management has largely consisted of attempting to prohibit cats from being loose altogether – an approach that’s incredibly unpopular with people who care for outdoor cats. DespiteĚý, few have been enacted.

Instead, we suggest prioritizing areas where wildlife is most at risk. For example, cities could create “no cat zones” near urban habitats, which would forbid releasing trap-neuter-return cats in those areas and fine owners in those areas who let their cats roam outdoors.

In Washington, D.C., this would includeĚýĚýlike Palisades or Buena Vista, as well as homes near parks like Rock Creek. As we see it, this targeted approach would have more impact than citywide outdoor cat bans that are unpopular and difficult to enforce.

Hard-line policies have done little to reduce outdoor cat populations across the U.S. Instead, we believe a data-driven and targeted approach to cat management is a more effective way to protect wildlife.

This article is republished fromĚýĚýunder a Creative Commons license. Read theĚý.

Sign up for our FREE morning newsletter and face each day more informed.

Sign up for our FREE morning newsletter and face each day more informed.

Support Independent, Unbiased News

Civil Beat is a nonprofit, reader-supported newsroom based in ±á˛ą·É˛ąľ±Ę»ľ±. When you give, your donation is combined with gifts from thousands of your fellow readers, and together you help power the strongest team of investigative journalists in the state.

About the Authors

-

I broadly study threats to urban wildlife, and possible strategies to overcome those threats using intentional public policy and urban planning. Much of my research focuses on outdoor cats, the impacts they have on wildlife, and management strategies we can employ in cities to reduce that impact.

I broadly study threats to urban wildlife, and possible strategies to overcome those threats using intentional public policy and urban planning. Much of my research focuses on outdoor cats, the impacts they have on wildlife, and management strategies we can employ in cities to reduce that impact. -

Our lab uses theories and principles in ecology and conservation science to sustain and restore biodiversity in urban ecosystems. We work to understand how urban environments – both the physical and social – shape species distributions, populations, communities, and behaviors. Through our research, we hope to better understand fundamental ecological processes in urban ecosystems and apply this knowledge to future urban planning. Our goal is to provide evidence-based solutions that simultaneously conserve biological diversity and improve the lives of urban residents.

Our lab uses theories and principles in ecology and conservation science to sustain and restore biodiversity in urban ecosystems. We work to understand how urban environments – both the physical and social – shape species distributions, populations, communities, and behaviors. Through our research, we hope to better understand fundamental ecological processes in urban ecosystems and apply this knowledge to future urban planning. Our goal is to provide evidence-based solutions that simultaneously conserve biological diversity and improve the lives of urban residents.