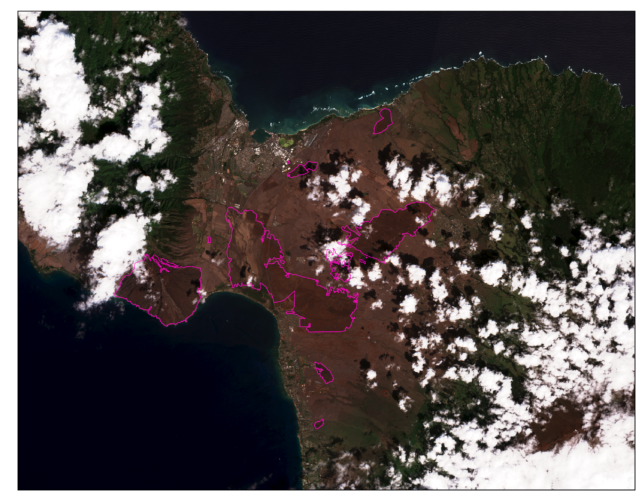

The recently organized a field tour of the Central Maui fires for state and county leadership to discuss solutions to Hawaii’s wildfire issues. The nearly 20,000 acres that burned this summer may be unprecedented for Maui, but reflect dramatic increases in wildfires across the state. This field trip aimed to bring forward ideas and experiences of fire responders, land managers, landowners and others who have been tackling this problem for years.

Most fires in Hawaii start in unmanaged nonnative grasslands and shrublands, which have dramatically expanded with declines in Hawaii’s agricultural “footprint” by more than 60% since the 1960s. The Central Maui fires are the most obvious consequence of this change. Other examples include 2018’s huge West Oahu fires and West Maui fires during Hurricane Lane, all on former plantation lands.

Much of the 4,600 acres that just burned at Maalaea (the fourth-largest incident there since 2006) were once ranch lands and sugarcane. This historical context makes it difficult to place singular blame for fire incidents, and also indicates that policies of “benign neglect” applied to large swaths of our watersheds aren’t working.

The field trip, however, offered some positive takeaways. Cooperation among firefighters, equipment operators and landowners is excellent. In addition to agreements between county, state and federal agencies, as one participant stated, “people just show up ready to help.”

Another point is most fires in Hawaii are quickly extinguished. Just 16 of Hawaii’s accounted for 95% of the 32,000 acres burned last year. In other words, our firefighters do their jobs well. But shifting conditions underfoot make their jobs more difficult and dangerous.

Limited access and water usually underlie larger fires. Abandoned agriculture allows fuel build-up, but also eliminates road maintenance, water, equipment and personnel that historically assisted firefighters. Responders on Maui also pointed to climate change. Firefighters at the Waiko Road Fire (Maui’s largest on record at 9,000 acres) saw fire behavior they “had never experienced before.” Along with high winds, temperature at Kahului topped 93 degrees that day, 9 degrees above average, with very low relative humidity (34%). The result was explosive fire growth with little chance for containment.

The evacuations and road and airport closures during these fires highlight the vulnerability of our communities and tourism-based economy. The Waiko Road Fire threatened Maui Electric Co.’s Maalaea Power Plant that supplies electricity to 80% of the island. The ecological impacts of fire are equally significant for local livelihoods and heritage. The wave of nonnative weeds that invade Hawaiian forests after fire completely transforms these ecosystems while restoration is slow and costly. Even in nonnative vegetation, fire can reduce groundwater recharge and dramatically increase sedimentation onto reefs.

As Hawaii’s ecosystems change with introduced species, unexpected impacts may emerge. Ranchers noted, for example, that the Maui fires drove hundreds of axis deer up the mountain, reducing forage for livestock.

Prevention is far less costly than fire impacts and solutions to reduce risk are relatively simple. Public education is critical to reduce ignitions.

For instance, torching abandoned cars is a key ignition source on Maui, so increasing awareness of the Junk Vehicle Assistance Program could have impact. For fuels, putting land back into agriculture, expanding livestock grazing, converting grasslands to less flammable vegetation, also conventional fuel breaks and prescribed burning, all reduce the potential for fires to ignite and grow.

Hazard Reduction

The key question is how do we sustain funding for mitigation?

The primary funding source, U.S. Forest Service grants, pits Hawaii applicants in competition with western states and each other. One response is to copy California’s state-funded grant program for mitigation projects. Unfortunately, there are more questions than answers: How can coordination during emergencies transfer to cooperation before fires? Can we incentivize versus regulate fire mitigation? Can we integrate fire risk into future planning and development?

As Hawaii’s ecosystems change with introduced species, unexpected impacts may emerge.

A key message of the field trip, and a fire management principle worldwide, is we all have a role to play: the public, homeowners, landowners and managers, researchers, planners, policymakers and responders. Short-term options, for example, include .

However, making our communities and landscapes more resilient over the long-term on all fronts — social, economic, and environmental — will take creative partnerships, increased valuation of land stewardship, and vision for what our future landscapes could look like.

Fire management offers insight into how we might respond to many societal challenges that will not improve without proactive intervention: community health and safety, equitable livelihoods and development, environmental degradation, and the big one, climate change.

For fire, the consequences of inaction are clear and multiple solutions exist, from fuel breaks to alternative land uses to restoring less flammable vegetation. These actions target fire, but can be designed to derive multiple benefits from the landscape.

The real challenge seems to be not just communicating the value of what we stand to lose, but reminding ourselves we can choose a better way forward.

GET IN-DEPTH

REPORTING ON HAWAII’S BIGGEST ISSUES

GET IN-DEPTH

REPORTING ON HAWAII’S BIGGEST ISSUES

Community Voices aims to encourage broad discussion on many topics of community interest. It’s kind of a cross between Letters to the Editor and op-eds. This is your space to talk about important issues or interesting people who are making a difference in our world. Column lengths should be no more than 800 words and we need a current photo of the author and a bio. We welcome video commentary and other multimedia formats. Send to news@civilbeat.org. The opinions and information expressed in Community Voices are solely those of the authors and not Civil Beat.

We need your help.

Unfortunately, being named a finalist for a Pulitzer prize doesn’t make us immune to financial pressures. The fact is, our revenue hasn’t kept pace with our need to grow,Ěý.

Civil Beat is a nonprofit, reader-supported newsroom based in ±á˛ą·É˛ąľ±Ę»ľ±. We’re looking to build a more resilient, diverse and deeply impactful media landscape, and we hope you’ll help by .