Editor’s Note: This is the first report in an ongoing series examining the challenges of recruiting and retaining teachers in Hawaii.

First-year Hawaii public school teacher Lydia Haff is as much a product of her West Oahu community as the ninth graders she teaches at Waianae High School.

She grew up in Makaha, where she still resides with her parents, going to the same beaches and visiting the same food trucks as her students.

âEveryday stuff,â as Haff refers to it. âKnowledge like that, it helps us connect.â

That shared context goes a long way at the Leeward Coast school where one-quarter of the teaching staff of 120 is emergency hires who don’t have a teaching license. There is also high turnover: just 45% of the teachers have been there five years or more, as of 2017-2018.

Haff, 23, who graduated from the University of Hawaii West Oahu with a teaching degree, said she’d prefer to still be at Waianae High â where many new and inexperienced teachers are assigned â five years down the road.

âI canât imagine teaching at any other school,â she said. âItâs really close to home, also it’s just really comfortable. It’s just easy for me to connect to the kids.â

That type of commitment is what the Hawaii Department of Education hopes to harness as it contends with a chronic shortage of qualified teachers that disproportionately hits low-income and remote area schools, according to a Civil Beat analysis of DOE data.

Tackling teacher recruitment and retention is one of the DOE’s main priorities for improving the school experience, with that include establishing “teacher academies” at the high schools, helping long-term educational assistants and substitutes obtain a teacher’s license and studying Hawaii’s teacher pay compared with other school districts.

But challenges abound:

- There is a heavy dependence on mainland hires, many of whom leave after a few years due to the hardship posed by the state’s high cost of living on a DOE teacher’s salary, or geographic isolation.

- Teachers are leaving the state at a higher rate than before: of the 1,116 teachers who separated from the Hawaii Department of Education in 2017-18, , a 70% increase from five years prior.

- This has created more vacancies. , there were 1,029 positions not occupied by a certified teacher, meaning those spots had to be filled by a substitute or an emergency hire â someone with a bachelorâs degree but no teaching credential.

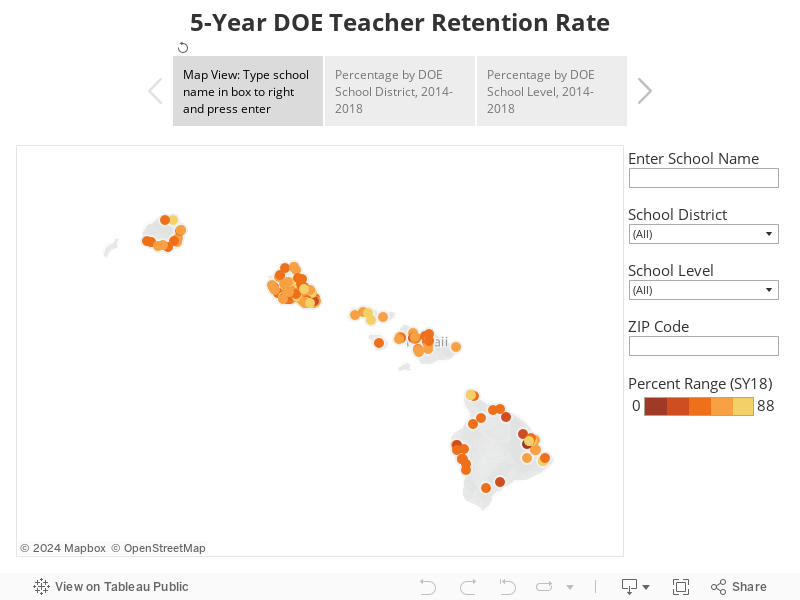

- On average, 51% of DOE teachers stayed at the same school five years or longer as of the 2018-19 school year â slightly higher than the national average, but falling short of the department’s goal .

Where The Shortages Exist

Civil Beat’s analysis of the 256 DOE public schools, excluding some small schools and the 36 public charter schools, found that the shortage of teachers, particularly experienced teachers, affects the school system unevenly.

Multi-level schools, typically K-12 and largely clustered on neighbor islands, are particularly hard hit, as are schools in remote, low-income areas. For instance, Paauilo Elementary and Intermediate and Kalanianaole Elementary & Intermediate on Hawaii Island saw five-year teacher retention levels of just 20% and 26%, respectively, in 2017-18.

Schools that relied on higher numbers of emergency hires — 20% or more of teaching staff — in 2017-18 include such rural Big Island schools as Konawaena Middle and Hookena Elementary. It also includes Leeward coast schools on Oahu like Waianae Intermediate and Waianae High.

By contrast, the statewide average in 2018 for emergency hires as a proportion of instructional staff was 4%.

Schools that see lower rates of teacher retention and greater numbers of emergency hires are all , where two-thirds to as much as 100% of the student population are low-income.

Elementary schools, on average, see higher five-year teacher retention rates and a lower percentage of emergency hires across the board. There’s also a higher percentage of fully licensed teachers at the elementary school level. For example, several elementary schools in the Honolulu district boasted the highest percentage of teachers staying five years or longer, including Lincoln Elementary in Makiki (88%) and Aina Haina Elementary (86%).

“Elementary schools tend to have a higher percentage of people who are highly qualified. There are less openings (at that level) so it’s more competitive,” said Corey Rosenlee, president of the Hawaii State Teachers Association.

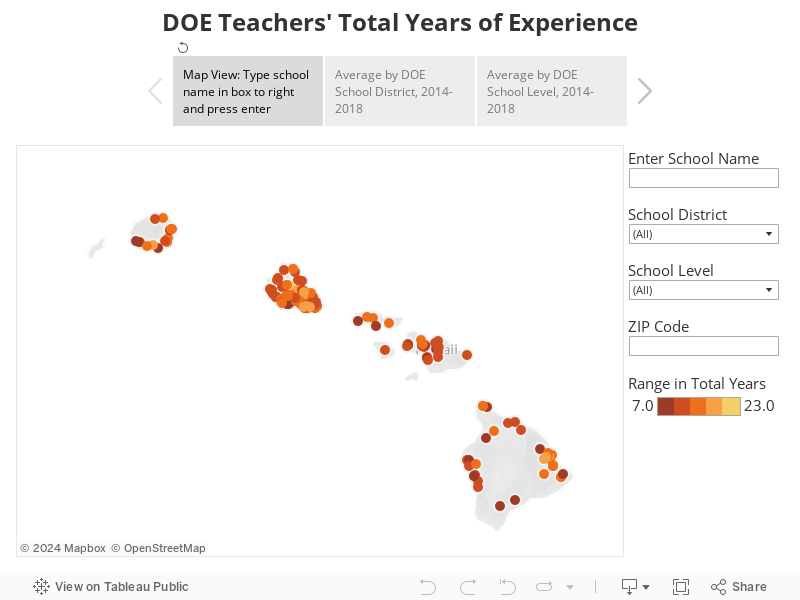

(How to use these charts: To view the data for an individual school, type the school name in the box on the right side and press enter. Then hover your cursor over the dot on the map.)Â

to view chart on mobile.

The difficulty of finding and keeping qualified teachers persists as the state struggles with meeting national benchmarks. According to the 2017 National Assessment of Educational Progress , known as “The Nation’s Report Card,” Hawaii’s eighth-grade math and reading scores and fourth-grade reading scores were “significantly lower” than the U.S. average.

Could longer-serving teachers translate to better academic success? The DOE’s  uses such indicators to measure student success. And while that high teacher turnover impacts student outcomes, it can also be disruptive to school climate, affect curriculum planning and sow apathy among students not so keen on attending school in the first place, according to experts.

“Turnover generally means replacing a moderately experienced teacher with a novice teacher. You take a hit on the average quality of teachers, organizational cohesion and planning and curriculum alignment,” said Matthew Kraft, associate professor of education and economics at Brown University.

Teacher turnover is “particularly problematic” at higher grade levels, he said.

High schools in Hawaii showing the highest graduation rates â of 90% or higher â are a mix of mostly Honolulu or Central Oahu District schools such as Kalani, Kaiser, Mililani, Radford and Moanalua. These schools rely less heavily on emergency hires and had a relatively high percentage of teachers reaching the five-year mark, according to DOE data.

to view chart on mobile.

High schools showing lower than average graduation rates include Kealakehe High and Kau High, both on Hawaii Island. They also have college-going rates of 50% or lower.

Many of these schools also encompass some of the most economically disadvantaged areas of Hawaii â much more so than urban Honolulu. The majority of DOE schools in the on the south Big Island, for instance, are .

The data shows a high likelihood that students at rural schools or lower-income areas are less likely to be taught by experienced, fully qualified teachers than elsewhere.

That’s a problem nationwide, not just in Hawaii.

âHigh poverty schools have double or more of what low poverty schools see in terms of annual teacher turnover,â said Richard Ingersoll, professor of education and sociology at the University of Pennsylvaniaâs Graduate School of Education. Additionally, the flow of teachers from high-poverty to low-poverty schools around the country is four times the rate as that in the other direction, he said.

The DOE recognizes the staffing challenges in remote areas. It a yearly $3,000 incentive bonus to licensed teachers teaching in hard-to-staff locations.

During a series of mainland recruiting trips this past spring, the DOE also adjusted its interviewing strategy to make candidate interviews “more personal” in hopes of finding a better fit, said Kerry Tom, director of the DOE personnel management branch.

“Before, the interviews were highly structured,” he said. “We didn’t really get to know the candidate and how they teach.”

They encouraged candidates to show portfolios of their work in addition to their resumes. Visiting places like New York, California, Texas, Oregon, Colorado and Georgia, the DOE rounded up about 300 teacher candidates, but are still working on finalizing offers.

The department expects it will need to hire the same number of teachers for 2019-20 as last year: about 1,291. It’s also streamlined the teacher application process by relying more on electronic documentation and removing requirements like original transcripts, Tom said.

According to Rosenlee, the problem isn’t recruiting, but retaining teachers. He said the state needs to pay Hawaii teachers more competitive wages and tie automatic salary increases to years of service.

“People say we have a teacher shortage problem in the United States. We don’t have a teacher shortage problem in the United States, we have a shortage of states that pay teachers well,” he said.

Bringing ‘A Measure of Stability’

Is Hawaii’s teacher shortage getting better or worse?

It depends on the geographic area of Hawaii and school type. All , with the exception of the Kauai district, saw the percentage of emergency hires grow from 2017 to 2018. High schools statewide experienced a 4% jump in emergency hires alone from 2014 to 2018.

Middle schools across the state also saw the percentage of teachers staying five years or longer slip during that same time period.

Waianae High presents one case study. In 2014, 18 of its 118 teachers, or 15%, were emergency hires. By 2018, 29 of its 120 teachers, or 24% of its teaching staff, were emergency hires.

The Leeward Coast school loses about 15 to 25 teachers yearly. It’s also a strong magnet for , the national program that sends participants to disadvantaged schools for two-year assignments, although many corps members choose to stay on longer.

Richard Stange, who is pursuing a master’s in education at UH West Oahu, volunteered to student teach at Waianae High after a UH instructor asked his students to consider that school for their training based on the high number of unlicensed teachers at the school.

âI was one of the candidates that raised my hand ⌠and here I am,â said Stange, 36, who is originally from New Jersey and moved to Hawaii 12 years ago. The Kapolei resident said teaching at Waianae has been “nothing but a positive learning experience.”

Waianae is particularly reliant on Teach For America â about 50 of its 120 teachers are TFA corps members or ex-corps members. Many are hired right out of college and have not gone through a state-approved teacher education program that is the first step to obtaining a teacher license, although many corps workers worked toward obtaining a full teacher credential during those two years.

The organization has had a longstanding presence in the islands. There are about 250 TFA teachers currently placed throughout the DOE. In the alone, there are 59 TFA members and 38 alumni in the schools.

âRetaining new teachers for two years is already a challenge for the DOE. Our program brings a measure of stability in that an overwhelming majority of our teachers fulfill their two-year commitment,” said Joshua Lee, TFA Hawaiiâs manager of external affairs.

Waianae High has its share of challenges, including one of the highest rates of chronic absenteeism in the state â 39% in 2018, when the state average was 20% â and among the lowest proficiency rates in math and language arts, based on the of key student indicators. While its graduation rate was fairly high at 78% in 2018, only about a third of students went on to college that same year.

Roughly 70% of the kids are low-income. Its population of Native Hawaiian students is among the highest in the state, at 65%.

“Frankly speaking, many of our students are incredibly bright but they struggle with some academic skills. So for them to really engage, you have to build a relationship with them,” said Michael Kurose, vice principal, during a recent principal panel for students pursuing teaching degrees in Hawaii.

His advice was to “be open.”

“You’re young, you obviously got into this profession to help students, help young people. There’s some schools you may not have on your radar, but you’d be amazed at what you can learn as an educator at some of these places,” he told them.

That challenge compelled Haff to teach at Waianae High, to debunk the stereotype that poor academic performance amounts to low student potential.

She said many teachers in training are reluctant to apply to jobs at the school and prefer positions at the neighboring .

The stigma associated with Waianae extended to her own family. Growing up, Haffâs home schools were Makaha Elementary, Waianae Intermediate and Waianae High. But her parents chose to send her from a young age to Myron B. Thompson Academy, a public charter school, because they were concerned with the area DOE schools’ performance rankings.

âI can see why it has a (bad) reputation, but it’s not true,â Haff, who is of mixed Okinawan Japanese, Native American and Caucasian ethnicity, said of Waianae. âWe have a really good program, we have a rigorous program.

“Our kids might be a little rough around the edges but they’ve got heart. It’s not something you find at every school,” she added.

to view chart on mobile.

‘More About The Fit’

There are also the outliers, such as Molokai High, located in one of the most isolated and economically stagnant areas of the state. Average family income is below the state average and close to 70% of the students are eligible for free or reduced lunch.

But its teachers do stay. During the 2017-18 school year, the small school â student enrollment of 315 âwas the best-performing high school among all the neighbor islands when it comes to low teacher turnover. Of its 24 teachers, 17 had stayed five years or longer — or 71% of the staff. That far outpaces the state average.

How did it accomplish that?

Principal Katina Soares, who grew up in the community, said the schoolâs secret to high teacher retention is strong ties to the community. Many of the schoolâs teachers are either from the island or have spouses that are from the area.

âIt really is more about the fit initially,â she said. âWeâre very careful to warn people, it’s not the place for everybody. You either fit or you don’t, you love it or you don’t.â

Despite the overarching challenges, DOE administrators champion the opportunity for newcomers to pursue employment in the public schools.

Cindy Covell, assistant superintendent for the Office of Talent Management, cited the new and direction of the schools under DOE leadership.

“We have so many great teachers in Hawaii doing so many great things and when you look at people who might be considering working for the Hawaii Department of Education, this is the time for them to come,” she said.

This story was produced with support from the Reporting Fellowship program.

Data visualizations were produced by Evan Mirolla, an education policy research specialist who recently obtained his master’s degree in education at the University of Washington College of Education, and edited by Civil Beat Data Reporting Fellow Carlie Procell.

GET IN-DEPTH

REPORTING ON HAWAIIâS BIGGEST ISSUES

GET IN-DEPTH

REPORTING ON HAWAIIâS BIGGEST ISSUES

Support Independent, Unbiased News

Civil Beat is a nonprofit, reader-supported newsroom based in ąá˛šˇÉ˛šžąĘťžą. When you give, your donation is combined with gifts from thousands of your fellow readers, and together you help power the strongest team of investigative journalists in the state.