A the state鈥檚 heavily criticized civil asset forfeiture program has cleared the Legislature, but now sits on the governor鈥檚 desk with no apparent signs of whether it will become law.

Supporters are urging Gov. David Ige to sign it while police and prosecutors, who would lose substantial amounts of money, want him to veto it.

The bill would change whose property can be forfeited and redirect the proceeds of forfeited property from the state Attorney General鈥檚 office to the general fund.

In fiscal year 2017, the estimated value of forfeitures ordered by law enforcement agencies across the state was about $661,000, according to the program’s . Honolulu and Maui County police departments were two of the biggest law enforcement beneficiaries that year.

Civil asset forfeiture, a practice used by law enforcement agencies to seize property they suspect has been used to commit crime, has drawn widespread criticism nationwide from across the political spectrum for what critics say is a lack of due process.

In February, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the Constitution sets limits on states鈥� and municipalities鈥� ability to seize property allegedly involved in crimes under the Eighth Amendment, which bars excessive fines.

One of the biggest changes the reform bill for Hawaii鈥檚 program would bring about, if signed into law, is to require a felony conviction before law enforcement officials can seize property. As it stands, state law allows agencies to take property without a court hearing or any criminal charges filed.

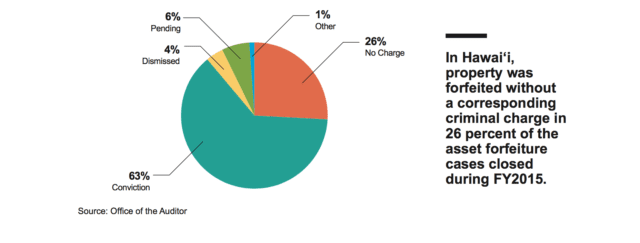

A June 2018 state audit of the current civil asset forfeiture program found that in 26% of the cases in fiscal year 2015, property was forfeited without a corresponding criminal charge. In another 4% of cases, charges were dismissed.

鈥淭hey took a whole bunch of assets from legally innocent people,鈥� said Rep. Joy San Buenaventura, a main sponsor of the bill. 鈥淚t鈥檚 basically legalized theft by the police, and that鈥檚 wrong.鈥�

The audit makes it evident that the program needs reform, she said. It also pointed out a slew of other problems, including failing to account for forfeited property, mismanaging program funds, failing to allocate 20% of the proceeds for drug prevention as is required by law, and failing to establish administrative rules.

“The audit shows that the attorney general was lackadaisical in handling assets,” San Buenaventura said.

Another major change would require the Attorney General鈥檚 office to use half of the forfeited property and proceeds from its sale on drug diversion programs, and the other half to go to the state general fund. Currently, half of the proceeds go to the AG’s office and the other half is split by police departments and prosecutors offices.

The AG鈥檚 office funds, in part, the program鈥檚 costs and the salaries of staff members with its 50% allocation. In February, the department 聽that the reform would 鈥済ut the revolving criminal forfeiture funds.鈥�

The Attorney General鈥檚 office did not respond to requests for an interview, but a spokesman told Civil Beat the department remains in opposition.

Law enforcement agencies can use the money to pay for such things as equipment and training. For example, the Honolulu Police Department, which opposed the bill, uses it to pay for and for officers who take police-related classes and training, according to Michelle Yu, an HPD spokeswoman.

鈥淚f House Bill 748 passes, this program will be discontinued,鈥� she said in an emailed statement. 鈥淗PD supports the veto of this bill.鈥�

Opponents of the program say it motivates law enforcement agencies to “police for profit.”

鈥淚f they鈥檙e relying on this in any way, then that鈥檚 a good reason for reform,鈥� said Mandy Fernandes, policy director for the American Civil Liberties Union of Hawaii. These funds are unstable by nature and vary year to year, and the fact that agencies stand to gain 25 percent of the proceeds might influence how the law is enforced.

Redirecting the proceeds to the state鈥檚 general fund would 鈥渄ilute the profit incentive,鈥� she said.

The Honolulu Prosecutor’s Office declined to comment, but previously told the Legislature in testimony that 鈥渃oncerns about 鈥榠nnocent owners鈥� being deprived of their property or 鈥榩olicing for profit鈥� are unfounded.鈥�

鈥淲e are confident that property is being seized and forfeited fairly and equitably and the abuse present in other jurisdictions simply does not exist here,鈥� the prosecutor鈥檚 office added.

The department plans on sending a letter to the governor urging him to veto the bill, spokesman Brooks Baehr said.

The governor has not indicated whether he intends to sign or veto the bill, his spokeswoman said. Ige has plenty of time to decide; if he plans to veto it, he just needs to let the Legislature know by June 24.

This is San Buenaventura’s second crack at getting an asset forfeiture reform bill passed. An attorney herself, she tried unsuccessfully in 2015, and she said she’s not surprised that prosecutors want to see the latest effort vetoed.

But she said she’s pushing on because it continues to be a problem in her district on the Big Island. She’s heard from families having their generators and vehicles seized, both of which they depend on for daily life, because someone in the family was suspected of a crime.

鈥淲e鈥檙e not saying to remove asset forfeiture altogether,鈥� she said. 鈥淲e鈥檙e just saying let鈥檚 make sure you鈥檙e taking them away from criminals and not innocent people.”

GET IN-DEPTH

REPORTING ON HAWAII鈥橲 BIGGEST ISSUES

GET IN-DEPTH

REPORTING ON HAWAII鈥橲 BIGGEST ISSUES

We need your help.

Unfortunately, being named a聽finalist for a聽Pulitzer prize聽doesn’t make us immune to financial pressures. The fact is,聽our revenue hasn鈥檛 kept pace with our need to grow,听.

Civil Beat is a nonprofit, reader-supported newsroom based in 贬补飞补颈驶颈. We鈥檙e looking to build a more resilient, diverse and deeply impactful media landscape, and聽we hope you鈥檒l help by .