The waves lap indifferently against the rocky revetment that guards a crumbling stretch of Kamehameha Highway in Kaaawa.

Immediately on the other side of this coastal road that connects several windward Oahu communities, workers are framing up the wooden beams of a new two-story house.

, a Honolulu residential development company owned by Amanda and Michael Gregg, bought the empty 6,000-square-foot lot in October for $410,000 and by November had a permit to build a 1,700-square-foot home on it.

No one from the company returned a call seeking comment for this story. But it’s clear they plan to sell the property as soon as it’s done. The Sturdy Foundations website advertises an oceanfront home, just steps from Kaaawa Beach. A slideshow features artist’s renderings and photos of a palm leaning over a smooth stretch of sand.

But on a recent Monday morning, there is little to no beach. The tides fluctuate, and there is sand at certain times, but the beach is disappearing as sea levels rise and erosion intensifies.

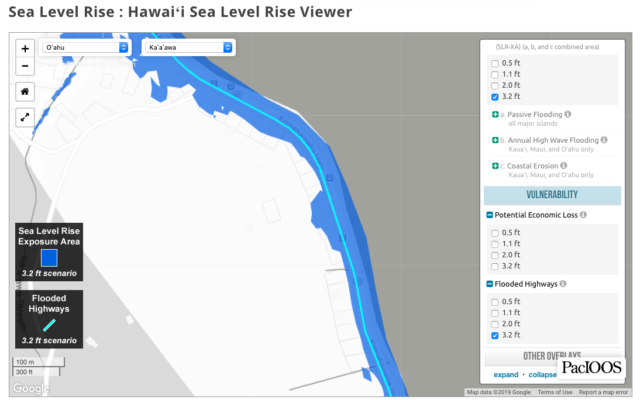

Scientists have projected that this stretch of highway will be at least partially flooded with just a half foot of sea level rise, forecast for 2030. When it rises 3 feet, expected by the end of this century or sooner, show the whole road and entire property will be underwater.

Now, Hawaii lawmakers are considering whether homeowners should have to tell buyers that their property is in a sea level rise exposure area — or SLR-XA as planners call it.

Related Stories

The state Climate Commission and top climate experts have all mandatory disclosure.

Department of Land and Natural Resources Chair Suzanne Case last month that it is critical for buyers to understand the hazards and risks they are assuming in purchasing oceanfront property, “in the spirit of transparency and disclosure and to support informed decision-making by buyers and government agencies.”

But the , representing 9,500 members, wants disclosure to remain voluntary.

Ken Hiraki, the group’s lobbyist, that the association opposed the bills because it would create an “unreasonable burden” on the typical seller, who he said lacks the capacity or ability to know if the property is in a sea level rise exposure area.

He also noted that the association already has an oceanfront property addendum to disclose pertinent information about owning a coastal home. He did not return a message seeking comment for this story.

Environmental groups, lawmakers and others note that  show the scale of potential flooding and erosion with sea level rise.

°Őłó±đĚý, published in December 2017 and adopted by the Climate Commission, includes a map viewer that lets users see the projected exposure areas at a half foot on up to 3.2 feet of sea level rise, as well as potential economic loss and flooded highways, passive flooding and coastal erosion.

Under legislation put forward this session, the Climate Commission would officially designate the exposure areas based on these maps.

It’s not unlike other disclosures that must be made when selling residential property, including special flood hazard areas, noise exposure areas and tsunami inundation zones.

Sen. Karl Rhoads, who introduced one of the mandatory disclosure bills, said he did not see the big deal in accessing a website to see if you live near an exposure area and having the buyers and sellers acknowledge that during the sale.

“Our whole response to global warming is a bit baffling to me,” he said. “It’s as close to an existential crisis as we’re likely to see, absent a nuclear exchange, and it just doesn’t feel like we’re taking it very serious.”

There’s a lot of coastal property at stake in Hawaii. The sea level rise report estimates the value of all structures and land projected to be flooded by a 3.2 foot rise in sea level at more than $20 billion.

The Gregg’s property in Kaaawa is hardly the only oceanfront home under construction. There’s one just up the road and many others around the state.Â

And people are continuing to buy oceanfront properties. Angela and Guy Farr bought the home next door to the Sturdy Foundations lot two years ago for $728,000, records show. They could not be reached for comment.

But not everyone dreams of living by the sea anymore.

Just up the road in Hauula, residents like Maureen Malanaphy are wondering how they will protect their properties from rising seas, more frequent storms and chronic erosion. Some neighbors are actively looking for places to move farther inland after spending a generation living on the coast and seeing firsthand how the environment has changed in recent years.

It’s spurred requests for seawalls and other emergency shoreline hardening. The DLNR has been under intense pressure from landowners, Case said, to permit shoreline protection such as seawalls and rock revetments, even though such armoring is discouraged by state laws, departmental administrative rules and county rules.

“The science is clear that installing coastal armoring on a chronically eroding beach typically leads to beach narrowing and loss,” she told lawmakers in testimony supporting the mandatory disclosure bills.

“There’s no escaping the fact that we’re going to have to deal with sea level rise in Hawaii.” — Rep. Nicole Lowen

Coastal changes aren’t just affecting homes and roads. Kualoa Regional Park, a couple miles south of Kaaawa, was once lined with postcard-perfect palms. The city cut many of them down when the erosion became too much to control. Stumpy root balls dot the shoreline instead. It’s a similar story on the North Shore.

University of Hawaii climate scientist Chip Fletcher, a lead author of the sea level rise report who’s been researching the issue for nearly three decades, said it’s incumbent upon lawmakers to have a greater sense of urgency in tackling the many problems related to sea level rise.

“It all boils down to we have to get out of the way,” Fletcher said. “And the longer you stay, the longer you are economically committed to this patch of ground which is in the end doomed.”

From year to year or even decade to decade, Fletcher said beaches change and sand moves. But he described that as noise superimposed on a trend.

“The beaches are going and going and going,” he said. “The trend is clearly shoreline recession.”

Contact Key Lawmakers

Senate President Ron Kouchi

senkouchi@capitol.hawaii.gov

808-586-6030

House Speaker Scott Saiki

repsaiki@capitol.hawaii.gov

808-586-6100

, introduced by Rhoads and four colleagues, would require all vulnerable coastal property sales or transfers to include a sea level rise hazard exposure statement to ensure new owners understand the risks. The latest draft had the law taking effect Nov. 1.

It passed the Senate unanimously and crossed over to the House last week. The bill’s road to passage was rough though, with three committee hurdles to jump before a final vote by the 51-member chamber.

Two related measures, Senate bills and , introduced by Sens. Gil Keith-Agaran and Jarrett Keohokalole, also crossed over to the House. House leaders referred them to four committees and while that can provide a more thorough vetting it’s often a kiss of death for bills.

The legislative session ends May 2, but the internal deadlines to keep the bills moving forward are coming up soon. It’s too late for many, absent some legislative maneuvering.

Thursday was the deadline for triple referral bills. Re-referrals, where committees are added or subtracted or redirected, are still possible though.

Senate Bill 1126 initially only had a double referral, which would have given the measure another week to have a hearing and pass out to the last committee, but then a third committee was added Tuesday. That moved the deadline up and gave the chairs of two committees just two days to hold a joint hearing, which didn’t happen.

Jodi Malinoski, policy advocate for the , said it’s still possible but unlikely a mandatory disclosure bill will pass this session as it’s just not a priority for House leaders.

“We’re not trying to push some grand obtuse idea. This is a priority for the Climate Commission,” she said. “But we’re a grassroots organization going up against a big association, and frankly big bags of money and political influence.”

The Hawaii Association of Realtors has donated more than $500,000 to at least 130 candidates over the past decade, show. The Sierra Club has given less than $500 to two candidates.

The House had moved forward with of a mandatory disclosure bill earlier this session but that one fizzled out in February.

Rep. Nicole Lowen, who co-introduced the measure and moved it through the Energy and Environmental Protection Committee she chairs, said she still supports mandatory disclosure but noted the testimony that contends disclosure may already be happening.

“Whether we need legislation or not is one question,” she said, adding that creating awareness about problems that might arise in the future is a first step toward implementing policies that encourage retreat from the shoreline in certain areas.

“There’s no escaping the fact that we’re going to have to deal with sea level rise in Hawaii,” she said.

GET IN-DEPTH

REPORTING ON HAWAII’S BIGGEST ISSUES

GET IN-DEPTH

REPORTING ON HAWAII’S BIGGEST ISSUES

We need your help.

Unfortunately, being named a finalist for a Pulitzer prize doesn’t make us immune to financial pressures. The fact is, our revenue hasn’t kept pace with our need to grow,Ěý.

Civil Beat is a nonprofit, reader-supported newsroom based in ±á˛ą·É˛ąľ±Ę»ľ±. We’re looking to build a more resilient, diverse and deeply impactful media landscape, and we hope you’ll help by .

About the Author

-

Nathan Eagle is a deputy editor for Civil Beat. You can reach him by email at neagle@civilbeat.org or follow him on Twitter at , Facebook and Instagram .

Nathan Eagle is a deputy editor for Civil Beat. You can reach him by email at neagle@civilbeat.org or follow him on Twitter at , Facebook and Instagram .