Editor’s Note: The authors delivered these remarks earlier this week as part of a panel discussion of small fishing communities at the International Union for Conservation conference in Honolulu.

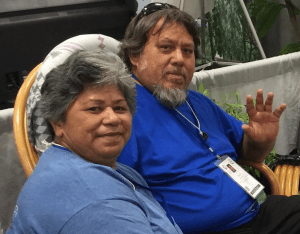

My wife, Glendora Alani Kenison and I are from Hookena Beach, South Kona, Hawaii Island. My wife’s great-grandfather was Hawila Kaleohano, and he was the head fisherman for the village of Hookena. Hawila taught his son Smith Kaleohano how to fish, and he in turn taught his son-in-law, my wife’s father, George Alani, how to fish.

What I know I learned from George Alani and his sons. We in turn continue to teach our children the fishing traditions of our kupuna. However, every generation loses some knowledge along the way. The reasons for this can’t be attributed to any one factor. But looking into the past may shed some light on one of the causes of the challenges we face as indigenous peoples.

Hawaiians were a very spiritual people, praying everyday to ask for guidance in living pono. When someone was ill, we would seek to heal spiritual obstructions before addressing physical symptoms. Hooponopono was the Hawaiian way to remove guilt and any bad feelings that might be burdening the person who was ill. As these beliefs were replaced by the new philosophies of other peoples who came here, that practice was separated and viewed in a different light.

Today, if someone is sick, the physical symptoms are treated. They are given medicines until the illness has abated. They are provided with advice on how to make changes that would prevent a recurrence of the illness or that might improve their quality of life in some way. However, the root of the problem may be something that is not fully acknowledged or easily remedied.

This is similar to our struggles to make laws, rules and policies that protect our resources. Often we only tackle the physical symptoms. The factors that created the challenges relating to the state of our natural resources often remain and cannot be healed with conventional methods.

When we look at a community and see the problems that exist, we throw money at the crises and try to fix the problems in the usual ways. We forget about the spiritual obstruction that may be the basic cause of our problems. We ignore the teachings of our kupuna and establish programs, buy technology and promote conventional methods for resolving conflicts in the management of our natural resources.

Hawaiian religion is generally perceived as being pagan, superstitious and un-Christian. Yet it sustained the Hawaiian people for hundreds of years. People too often regard the past as having no bearing on the problems we face today. Hawaiians however understand that the aina is a living entity and know that the past cannot be ignored. Our belief system sees our spiritual well-being as being one with the health of the aina.

I recently asked our community to seek out someone to perform a cleansing for our aina – hookena. It was met with resistance because of the changes in the ways that we perceive what a healthy condition is, and the approach we have grown used to taking to address challenges. When you look at Hookena Beach and see the beautiful sandy shore and dappled waters, one is made to feel good because of the physical beauty of this place. However, our perception is limited by the knowledge we have, and people are unable to understand the true picture if their scope of understanding is artificially constrained.

Hawaiian religion is generally perceived as being pagan, superstitious and un-Christian. Yet it sustained the Hawaiian people for hundreds of years.

Like our ancestors, we must first address the spiritual challenges we face before we create laws, rules and regulations that will enhance resource conservation and protect the aina, our culture and the future of our people.

What harm would a spiritual cleansing cause? Would it seem as if we are avoiding responsibility for the social, economic, and political changes that have shaped our way of understanding the problems we face today? Maybe that is the reason why we are made to feel guilty about why our people are burdened with alcohol, drug abuse and poverty. We attack the problem with money and adopt the solutions implemented by a group of people who may have no ties to the aina.

In the past, after the new religions were introduced, Hawaiians were generally considered to be a lazy people who were only pleasure-seeking idolaters who shunned responsibility. Because of the structure of the kapu system they were not good businessmen and refrained from working in the sugar and pineapple plantations for economic gain. A system that guided them for hundreds of years was suddenly displaced by a new order that was foreign to them.

The new cultures that became dominant left Hawaiians without an effective way to participate in the changing political makeup that wrought changes in how people cared for the land and ocean. The traditional management practices that had preserved the resources for each generation were abolished in favor of a system that placed the desires of one faction with no historical ties to the land above the health of a resource and the needs of the people who depend on them for sustenance and continued cultural practice.

It is not good to place the blame on any one group for the plight of our aina. Rather, let us open our minds to solutions that may have a positive effect on our efforts to protect the aina. Look inside of yourselves to free your mind from the obstacles that may block effective answers to protecting and perpetuating the resources and host culture of Hawaii Nei.

GET IN-DEPTH

REPORTING ON HAWAII’S BIGGEST ISSUES

GET IN-DEPTH

REPORTING ON HAWAII’S BIGGEST ISSUES

Community Voices aims to encourage broad discussion on many topics of community interest. It’s kind of a cross between Letters to the Editor and op-eds. This is your space to talk about important issues or interesting people who are making a difference in our world. Column lengths should be no more than 800 words and we need a current photo of the author and a bio. We welcome video commentary and other multimedia formats. Send to news@civilbeat.org. The opinions and information expressed in Community Voices are solely those of the authors and not Civil Beat.

We need your help.

Unfortunately, being named a finalist for a Pulitzer prize doesn’t make us immune to financial pressures. The fact is, our revenue hasn’t kept pace with our need to grow,Ěý.

Civil Beat is a nonprofit, reader-supported newsroom based in ±á˛ą·É˛ąľ±Ę»ľ±. We’re looking to build a more resilient, diverse and deeply impactful media landscape, and we hope you’ll help by .