Elton Kinoshita did everything he could think of last year to find enough qualified teachers to fill all the unexpected vacancies at Lanai High and Elementary School.

The second year principal scoured state Department of Education applicant lists, talked to substitute teachers about working full time, and asked community members to network on the school’s behalf. When classes started without even enough substitute teachers to fill in, Kinoshita picked up a math textbook and asked students for patience.

“I told the students the last time I took pre-calculus was September 1975,†Kinoshita recalled. “One of them said, â€کMy mom wasn’t even born then.’â€

The students laughed, Kinoshita said, but the problem was serious.

Teacher shortages have become a pressing national issue in recent years, as states grapple with an increasing number of young teachers fleeing the profession after only a few years in the classroom.

Waianae High School hired 16 new teachers this year but is still searching for eight more.

Cory Lum/Civil Beat

Hawaii has worked to decrease the number of annual vacancies and emergency hires of uncertified teachers by creating alternative paths to licensing, increasing bonuses for teachers hired in hard-to-staff areas, and strengthening mentoring and support for new teachers.

But recruiting — and then keeping — teachers remains a pronounced challenge in many of the state’s most remote and low income schools.

“The constant turnover, especially in poor communities, is very demoralizing for students and even teachers.” — Disa Hauge, principal, Waianae High School

Kinoshita taught high school math for the first two months of the 2014-15 school year. His vice principals taught elementary school classes. They completed administrative work after school was dismissed, and then prepped at night to lead classes they hadn’t taught in years — if ever. They worked late. They worked weekends.

This year things are better, Kinoshita said. “Better” is a relative term, though. Lanai is currently short three teachers, and is one of dozens of schools across the state trying to recruit staff for a school year that has already started.

As of July 29, the Department of Education had hired about 700 new teachers for the 2015-16 school year, including 231 emergency hires. Many more teachers are needed.

Waianae High School hired 16 teachers this year and is still searching for eight more. Molokai Middle needs two special education teachers. Lahaina Intermediate on Maui is missing a language arts teacher, two social studies teachers, a special education teacher, a math teacher and a health teacher.

It’s a challenge that strains administrators, costs the state millions of dollars every year, stymies efforts to launch new programs, and leaves some students sitting in classes taught by underqualified or temporary teachers.

“It’s frustrating,†said Lindsay Ball, superintendent of the Hana-Lahainaluna-Lanai-Molokai Complex Area. “Our principals are working very hard to fill vacancies and positions … but what can you say when you don’t have anyone and you are just hopeful you have enough substitutes?â€

Hundreds More Likely Needed

Hawaii has been facing a teacher shortage for more than two decades.

In the early 1990s, local schools desperately needed more special education teachers. A few years later math and science teachers were added to the list. This year the state reported a shortage of teachers for English and reading, Hawaiian, Hawaiian immersion, mathematics, science, special education and vocational and technical classes.

High teacher turnover is a big part of the problem. About 10 percent of teachers switch schools, move away or leave the profession each year. That means only about 60 percent of teachers in the state have been at the same school for five or more years.

“Talk about inequality. There is a moral wrong when the most needy students are also the most likely to have inexperienced teachers.†— Corey Rosenlee, teachers union president

In other subjects, like Hawaiian, there simply aren’t enough trained teachers to meet the growing demand.

New Hawaii State Teachers Association President Corey Rosenleeآ links teacher turnover to both challenging teaching conditions and teacher pay that, when the cost of living is factored in, ranks among the lowest in the country.

“The constant turnover, especially in poor communities, is very demoralizing for students and even teachers,” Waianae High School Principal Disa Hauge said. آ “It makes you feel you are not valued or important if people are constantly آ leaving you.â€

The total number of vacancies for 2015-16 won’t be known until after enrollment counts are complete, Barbara Krieg, assistant superintendent for the DOE’s Office of Human Resources, said in an email.

If past years are any indicator though, schools could need to hire anywhere from 400 to 800 more teachers before the year is over.

There are currently about 665 qualified applicants in the DOE hiring pool who can be referred to schools for recruitment, DOE spokeswoman Donalyn Dela Cruz said.

Harder-to-Staff Schools

School administrators stress that regardless of the shortage, they aren’t just looking for any teachers — they are still committed to finding the best and the brightest.

But an an analysis of staffing in the state raises some red flags.

Nationwide, 56 percent of public schoolteachers have an advanced degree. In Hawaii 36 percent of teachers do.

While 93 percent of classes in the state are taught by teachers deemed to be “highly qualified†under No Child Left Behind standards, in harder-to-staff schools that number plummets to as low as 56 percent. Schools in poorer and more remote areas are also more likely to have a higher percentage of young teachers, unlicensed teachers, and emergency hires.

“Talk about inequality,†Rosenlee said. “There is a moral wrong when the most needy students are also the most likely to have inexperienced teachers.â€

It also costs the state a lot of money to constantly recruit and train so many new teachers. A study last year by the Alliance for Excellent Education estimated the costs of teacher attrition in Hawaii to be $6.2 to $13.5 million a year.

Growing Teachers in Hawaii

The DOE is largely in charge of screening and vetting teachers. It sends administrators to other states on recruiting trips, processes applications, and then sends lists of qualified applicants to schools.

Not all applicants are willing to go to areas like the Waianae Coast or Lanai, Nanakuli-Waianae Complex Area Superintendent Ann Mahi said.

“It is so far away from where people live, it may not be the first area people think about for a position,†Mahi said. “We are in competition with other schools in Oahu.â€

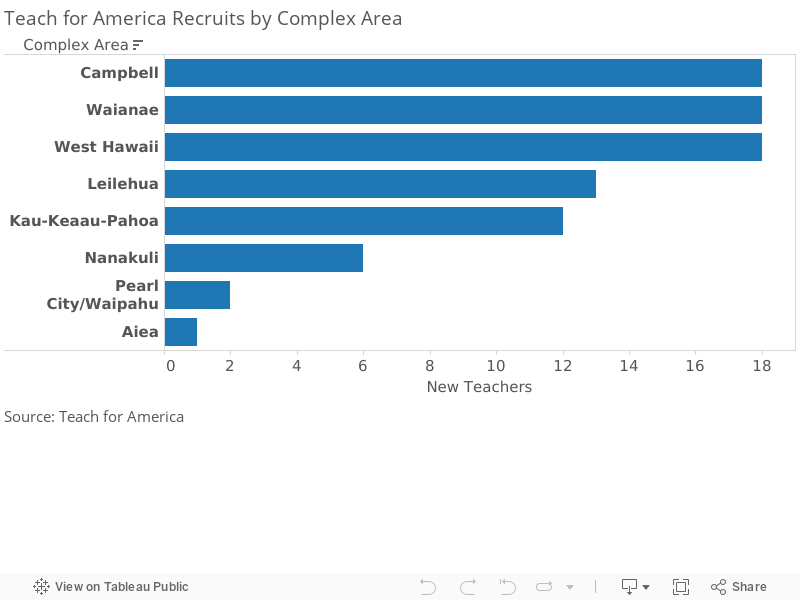

Mahi’s schools turn to mainland recruits and programs like Teach for America to fill many of their vacancies. These teachers are good, Mahi said, but they often stay only a few years before moving back home.

“They have family obligations and go back,†she said.

While Mahi is trying to address that problem by creating networking and support programs that will help mainland teachers grow local roots, other schools try to tap into an extended community network in hopes of finding teachers who will not only come to remote parts of the state, but will stay.

Last year Kinoshita hired a special education teacher from Ohio, who was then able to convince a friend to move to the island to teach kindergarten this year.

Lanai’s new math teacher went to college in Oregon with a Lanai native who persuaded her of the island’s beauty. When a new minister moved to the island from Pennsylvania, the school convinced her husband — a former general manager for a distribution plant — to teach sixth grade science and math as an emergency hire.

Lanai is lucky in in some ways, Kinoshita said, because it is one of the few areas in the state that can offer teachers DOE-owned housing to rent.

Although all of these efforts are helping decrease shortages in some areas, the problem really won’t be solved until Hawaii convinces more of its own young people to become teachers, Mahi said.

A new program at Waianae High School is aimed at doing just that. Through the New Teacher Academy, which launched last week with an inaugural class of 30, students will get firsthand experience in the education field during their junior and senior years.

The school is also partnering with Leeward Community College and UH West Oahu to develop a smooth postsecondary pathway for students who decide they want to continue pursuing a career in education.

“If we are not going to get staff from anywhere else, we are going to grow our own,†said Waianae’s Hauge. “Our kids can do amazing jobs as teachers and counselors and administrators.â€

GET IN-DEPTH

REPORTING ON HAWAII’S BIGGEST ISSUES

GET IN-DEPTH

REPORTING ON HAWAII’S BIGGEST ISSUES

Support Independent, Unbiased News

Civil Beat is a nonprofit, reader-supported newsroom based in ±ل²¹·ة²¹¾±ت»¾±. When you give, your donation is combined with gifts from thousands of your fellow readers, and together you help power the strongest team of investigative journalists in the state.

About the Author

-

Jessica Terrell is the projects editor at Civil Beat. You can reach her by email at jterrell@civilbeat.org.

Jessica Terrell is the projects editor at Civil Beat. You can reach her by email at jterrell@civilbeat.org.